Works of Henri Cartier-Bresson And Irving Penn

Henri Cartier-Bresson (French, 1908 - 2004), An astrologer's shop in the mill workers' quarter of Parel Bombay,

Maharashtra, India 1947, gelatin silver print,

13.78 x 20.67 in. (35 x 52.5 cm)

©Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

Think of the spectrum of photographic images from the candid to the posed. The unposed shots are untouched by artifice - a slice of reality frozen in time. The photographer looks and waits until he/she senses a picture is there. The moment is seized. The button pressed. The shutter released. The photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson (French, 1908 - 2004) called this the "decisive moment." No arranged positioning of models and clothing but life caught in all its actuality. Traveling throughout the world, he took pictures. No matter where, in Mexico, India, China, Japan, Indonesia or Russia, Cartier-Bresson's eye was focused on capturing anything around him that he intuitively saw as an instant of pictorial worth.

Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009), Three Dahomey Girls, One Reclining,

1967, printed 1980, platinum-palladium print,

Image: 19 11/16 x 19 11/16 in. (50 x 50 cm.) Sheet: 22 x 24 15/16 in. (55.9 x 63.4 cm.)

Mount: 22 x 26 in. (55.9 x 66 cm.) Overall: 22 x 26 in. (55.9 x 66 cm.)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

IP .155

The working methodology of the photographer Irving Penn (American, 1917 - 2009) was quite different. He chose to set up his subjects. Backdrops, studio and assistants were employed to make the photos he sought. Placement, garments and gestures were adjusted to indicate his specific point of view. Penn seemed to leave very little to chance. Whether on location in Cuzco, Peru, New Guinea in the South West Pacific or Guelmim, Morocco on the edge of the Sahara, he set up a tent/studio complete with lighting enhancement equipment and attendants.

These two dissimilar but equally effective photo taking strategies are illustrated in two New York City exhibitions: Henri Cartier-Bresson: India In Full Frame at the Rubin Museum of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Irving Penn: Centennial. The shows not only give pleasure in viewing superb, informative pictures but also stimulate the consideration of underlying beliefs that permeate the making of these images.

Henri Cartier-Bresson (French, 1908 - 2004),

Gandhi dictates a message, just after breaking his fast Birla House,

Delhi, India 1948, gelatin silver print,

13.78 x 20.67 in. (35 x 52.5 cm)

13.78 x 20.67 in. (35 x 52.5 cm)

©Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

The Rubin Museum's exhibit displays Cartier-Bresson prints concerning India. Many focus on Mahatma Gandhi and his funeral. In 1947 Henri Cartier-Bresson co-founded with Robert Capa and three other photographers the photo agency Magnum Photos. Later that year, he made the first of six extended trips to India to document the major changes taking place in the aftermath of the country's independence from Britain.

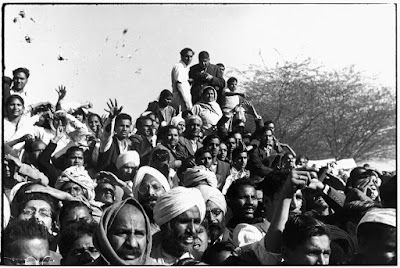

On January 30, 1948 Cartier-Bresson met with Gandhi and took some of the last pictures of him just before his assassination. The photographs he made of Gandhi's funeral and the nation's outpouring of grief appeared in Life magazine. They became one of the most acclaimed photojournalistic reports ever published.

The Rubin show also includes everyday scenes of life in various Indian states, politicians, refugees as well as magazines illustrated with Cartier-Bresson's work. Cartier-Bresson was not interested in photographic equipment or the print making process. He did not use aides such as tripods, reflectors or flash. He relied on available light. He did not work in the darkroom. He wanted his shots produced in full frame without cropping. Black borders about prints indicate the whole negative was printed. He sent his negatives directly to the editors. He composed with his camera and what he shot was what was produced.

On January 30, 1948 Cartier-Bresson met with Gandhi and took some of the last pictures of him just before his assassination. The photographs he made of Gandhi's funeral and the nation's outpouring of grief appeared in Life magazine. They became one of the most acclaimed photojournalistic reports ever published.

Henri Cartier-Bresson (French, 1908 - 2004), Gandhi's funeral. Crowds gathered between

Birla House and the cremation ground, throwing flowers Delhi,

Birla House and the cremation ground, throwing flowers Delhi,

India, 1948, gelatin silver print,

13.78 x 20.67 in. (35 x 52.5 cm)

13.78 x 20.67 in. (35 x 52.5 cm)

©Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

The Rubin show also includes everyday scenes of life in various Indian states, politicians, refugees as well as magazines illustrated with Cartier-Bresson's work. Cartier-Bresson was not interested in photographic equipment or the print making process. He did not use aides such as tripods, reflectors or flash. He relied on available light. He did not work in the darkroom. He wanted his shots produced in full frame without cropping. Black borders about prints indicate the whole negative was printed. He sent his negatives directly to the editors. He composed with his camera and what he shot was what was produced.

Henri Cartier-Bresson (French, 1908 - 2004), Kathakali dance drama.

A guru teaches the stories of the Ramayana and the MahabharataCheruthuruthi,

Kerala, India, 1950, gelatin silver print,

9.25 x 13.78 in. (23.5 x 35 cm)

9.25 x 13.78 in. (23.5 x 35 cm)

©Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos

He rarely worked with color film. The colors in nature, he held, were difficult to reproduce on a printed surface. Furthermore, he thought color was hard to control and the film's speed limitations produced effects that displeased him. For Cartier-Bresson, life and movement were better caught using black-and-white film.

One of Cartier-Bresson's Leica 35mm rangefinder cameras is on display. The Leica with a 50mm lens was the photographer's inseparable companion. He purchased his first one in 1932. He wanted the smallest camera possible that was capable of photographic precision. The Leica, hand-held, small and light, was easy to carry and conceal. He would use black tape to cover the camera's shiny parts. Unnoticed, he could shoot pictures of people and they would not change their behavior knowing they were being photographed. He was, above all, a photojournalist.

Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009), Rochas Mermaid Dress (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn),

Paris, 1950, printed 1980, platinum-palladium print,

Image: 19 7/8 x 19 11/16 in. (50.5 x 50 cm.) Sheet: 25 x 22 in. (63.5 x 55.9 cm.)

Mount: 26 1/8 x 22 in. (66.3 x 55.9 cm.) Overall: 26 1/8 x 22 in. (66.3 x 55.9 cm.)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

IP .131

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

IP .131

Penn, on the other hand, needed to be noticed. He was a photographer/director who set up all his scenes. The show at the Metropolitan Museum is the most comprehensive Penn retrospective to date. Organized by themes, in some 19 sections, the display makes manifest the depth and breadth of this photographer's artistry.

Like Cartier-Bresson, he studied art and obtained his first camera in the 1930s, a twin-lens Rolleiflex in 1938. The exhibition opens with one of Penn's Rolleiflex cameras that he acquired in 1964. It is topped with a modified Hasselblad viewfinder and mounted on a tiltall attached to a table tripod of Penn's design. The Rolleiflex was Penn's camera of choice. This sturdy instrument was difficult to hide. This was fine for Penn's technique of picture taking.

Like Cartier-Bresson, he studied art and obtained his first camera in the 1930s, a twin-lens Rolleiflex in 1938. The exhibition opens with one of Penn's Rolleiflex cameras that he acquired in 1964. It is topped with a modified Hasselblad viewfinder and mounted on a tiltall attached to a table tripod of Penn's design. The Rolleiflex was Penn's camera of choice. This sturdy instrument was difficult to hide. This was fine for Penn's technique of picture taking.

Irving Penn On Location in Morocco, 1971, 8mm film footage,

shot by Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn in 1971,

shows Irving Penn at work in his portable studio on location in Morocco.

On view at the exhibition, Irving Penn: Centennial*,

April 24 - July 30, 2017, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Video: YouTube.com

A Rolleiflex is held or placed at waist-level. The photographer looks down into its viewfinder. What is seen is exactly what you record the instant the shutter release button is pressed. Although left to right is reversed, the image seen is upright. Penn's and Cartier-Bresson's choice of cameras reflect two approaches to photo making.

Irving Penn, (American, 1917–2009), Ingmar Bergman, Stockholm,

1964, printed 1992 Gelatin silver print,

Image: 15 1/16 x 14 15/16 in. (38.3 x 37.9 cm.)

Sheet: 15 1/16 x 14 15/16 in. (38.3 x 37.9 cm.)

Mount: 16 15/16 x 16 15/16 in. (43.1 x 43.1 cm.)

Overall: 16 15/16 x 16 15/16 in. (43.1 x 43.1 cm.)

Promised Gift of The Irving Penn Foundation

IP .080

Penn's interest in equipment and printmaking was quite different from Cartier-Bresson's. Penn worked with his negatives, manipulating exposures, experimenting with chemicals and making pictorial adjustments. He was an outstanding craftsman and could produce a variety of quality prints from a single negative.

Irving Penn (American, 1917–2009), After-Dinner Games, New York,

1947, printed 1985, dye transfer print,

Image: 22 3/16 x 18 1/16 in. (56.4 x 45.8 cm)

Sheet: 23 7/8 x 20 1/16 in. (60.6 x 50.9 cm)

Overall: 23 7/8 x 20 1/16 in. (60.6 x 50.9 cm)

These two photographers are giants in their fields yet each had a very different vision of how to make pictures. You will leave the exhibitions thinking about their work and thinking about how you go about viewing.

✦✦✦✦✦✦✦✦✦✦✦✦

*The following is the wall text for the At Work in Morocco, 1971 film footage, on exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Irving Penn: Centennial, April 24 - July 30, 2017:

"This rare film footage of Penn at work inside his custom-made, portable tent studio was recorded by Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn in the Moroccan town of Guelmin; the sitters are members of the nomadic Tuareg peoples (Berbers). Most of the figures in indigo blue garments are guedras, or female dancers. Penn’s wife appears in a pink bandana."

**Due to popular demand, the Rubin Museum of Art's Henri Cartier-Bresson: India In full Frame scheduled to close on September 4, 2017 was extended on August 1, 2017 until January 29, 2018.

✦✦✦✦✦✦✦✦✦✦✦✦

Henri Cartier-Bresson: India In Full Frame

April 21 - January 29, 2018**

150 West 17th Street, Manhattan

Hours:

Monday 11:00 am – 5:00 pm

Tuesday Closed

Wednesday 11:00 am – 9:00 pm

Thursday 11:00 am – 5:00 pm

Friday 11:00 am – 10:00 pm

Saturday/Sunday 11:00 am – 6:00 pm

Closed on Christmas, Thanksgiving, and New Year’s Day.

Irving Penn: Centennial

April 24 - July 30, 2017

1000 Fifth Avenue, Manhattan

Hours:

Sunday - Thursday 9 am - 5:30 pm

Friday and Saturday 10 am - 9 pm

Closed Thanksgiving Day, December 25,

January 1, and the first Monday in May.